Popular Sovereignty and Political Form, 1250-1600

Why do appeals to the sovereignty of the people so often culminate in the concentration of authority in a single office? In my first book project, Popular Sovereignty and Political Form, 1250-1600, I identify a longstanding intellectual tradition in which the doctrine of popular sovereignty was designed to legitimize—and even require—unified executive authority.

Building on my recent work on Aristotle (“Aristotle on Political Friendship and Equality,” History of Political Thought, 2023), I examine how medieval commentators synthesized Aristotelian conceptions of the “rule of the multitude” with monarchical models of government. Scholastic political theorists such as Thomas Aquinas, Giles of Rome, and Peter of Auvergne argued that a populus or multitudo can only attain substantial unity through the directive guidance of a single princeps. On this view, popular sovereignty not only permits unified executive authority, but conceptually demands it. I follow this line of argument into the Italian Renaissance, where humanists such as Francesco Patrizi of Siena synthesized Aristotelian conceptions of the multitude with Roman imperial jurisprudence. My survey of Quattrocento treatises reveals that this ideological synthesis was not an exception, but the norm among humanist political theorists.

In the second half of Popular Sovereignty and Political Form, I focus on two canonical Renaissance political thinkers who adopted competing stances on popular sovereignty: Niccolò Machiavelli and Jean Bodin. In “Machiavelli Against Sovereignty” (Political Theory, 2024), I argue that Machiavelli’s Discourses on Livy critique the doctrine of popular sovereignty as a means of legitimating princely absolutism. My book expands on that claim, offering a novel interpretation of Machiavelli’s concept of the “civil principality” in The Prince. I conclude with a detailed study of Bodin’s République. Building on my forthcoming contribution to The Cambridge History of Democracy, I show that Bodin’s theory of popular sovereignty inherently tends towards Caesarism. This finding calls for a reassessment of Bodin’s legacy in modern democratic thought—a project I take up in my second book project.

Absolute Democracy

Democratic theory has always maintained an uneasy relationship to constitutionalism. In recent years, that relationship has grown especially strained. Contemporary political theorists such as Jeremy Waldron and Sheldon Wolin argue that constitutionalism—the limitation of political power by fundamental law—is inimical to popular sovereignty. Yet we lack a robust theoretical model of non-constitutional democracy. To this end, my second book project, Absolute Democracy, uncovers an overlooked tradition of democratic absolutism.

The first half of this book will challenge the historiographical claim that early modern absolutism was originally a theory of monarchy, which was later adapted for democracies. In fact, many early modern political philosophers understood democracy, rather than monarchy, as the paradigmatic model of absolute power. This logic is evident in Thomas Hobbes, who contends that the absolute character of sovereignty is most apparent in a popular assembly. Baruch Spinoza takes this view even further, arguing that democracy is the only “completely absolute state”—since it is the only one in which the multitude wills with “one mind.” This tradition culminates in Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose concept of the general will requires a unity so total that it can only be achieved by a lawgiver capable of refashioning human nature.

The second half of this book will study the early twentieth-century revival of absolute democracy among theorists of the revolutionary left and the authoritarian right. While Marxist-Leninists asserted that the dictatorship of the proletariat constituted a higher form of democracy, fascist propagandists argued that the true realization of popular sovereignty would require the overcoming of liberal institutions that impede the formation of the general will. The latter argument finds its clearest expression in the work of Carl Schmitt, who drew on theorists such as Bodin and Rousseau to develop an anti-liberal theory of democratic absolutism. My book culminates in a study of Schmitt’s engagement with the Bodinian theory of popular sovereignty, drawing on previously unstudied archival documents obtained from the Landesarchiv Nordrhein-Westfalen. By reconstructing the genealogy of absolute democracy, this project reveals how the radicalization of democratic principles can paradoxically lead to their disfigurement and perversion.

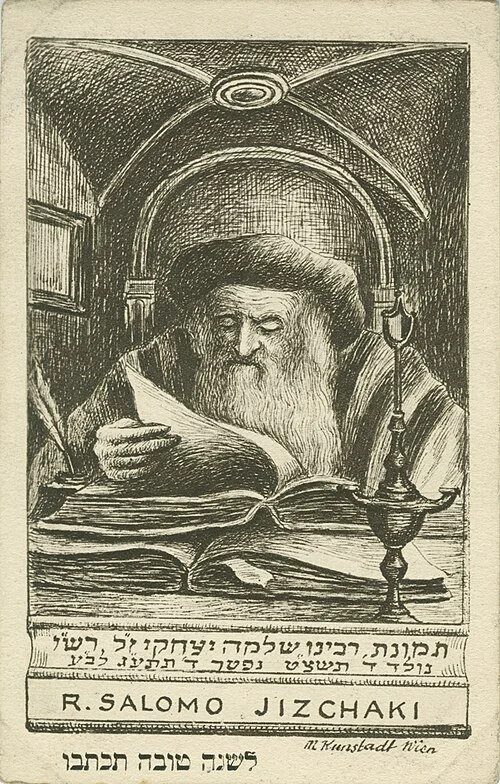

Bodin’s Political Hebraism

In an ongoing study of Jean Bodin’s political Hebraism, I examine the Jewish and Hebraic sources underlying his celebrated definition of sovereignty. Bodin’s appeal to the Hebrew phrase תומך שבט (tomech shevet, lit. “the holder of the scepter”)—a rare biblical expression associated with the bearer of royal authority—has never been fully explained. I argue that this term provided Bodin with a conceptual bridge between human and divine sovereignty, allowing him to formulate a theory of “absolute” political power that remained embedded within a theological order. At the same time, I show that Bodin treated the Hebrew commonwealth as a model of a just political order, in which human authority is both absolute within its sphere and accountable to a higher law.